Autour de KWY : 1958 – 1964

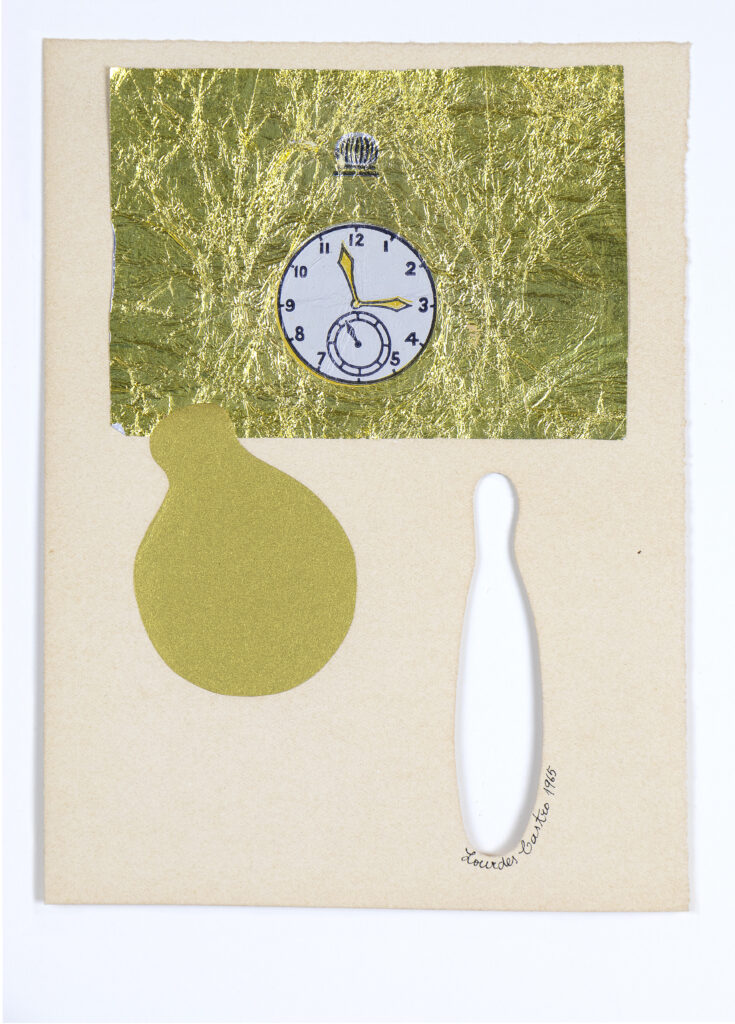

Manuel Alvess, René Bertholo, Lourdes Castro, Christo, António Costa Pinheiro, Gonçalo Duarte, José Escada, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, João Vieira, Jan Voss

Curated by Anne Bonnin

October 4 – October 26

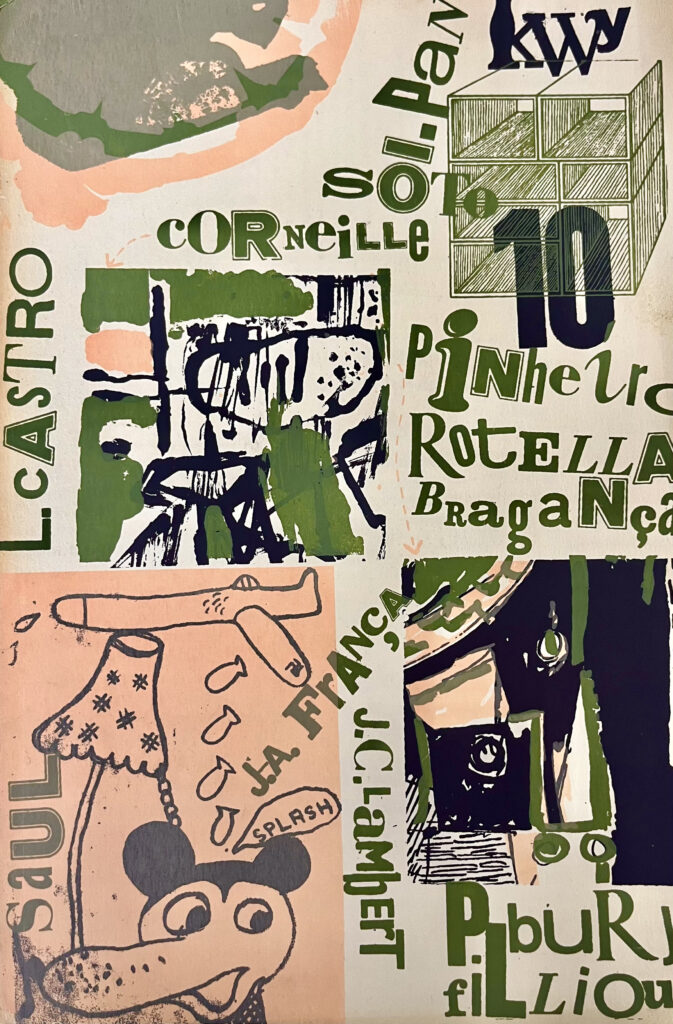

The KWY magazine (1958-1964) was a singular editorial adventure led in Paris by 8 young foreign artists, newly arrived in the capital. Its founders were Portuguese artists Lourdes Castro, René Bertholo, Costa Pinheiro, Gonçalo Duarte, José Escada and João Vieira, soon joined by Bulgarian Christo and German Jan Voss. They were exiles, some fleeing a dictatorship, others a country ravaged by war and Nazism. They chose to settle in Paris, which then radiated the aura of a cosmopolitan cultural capital.

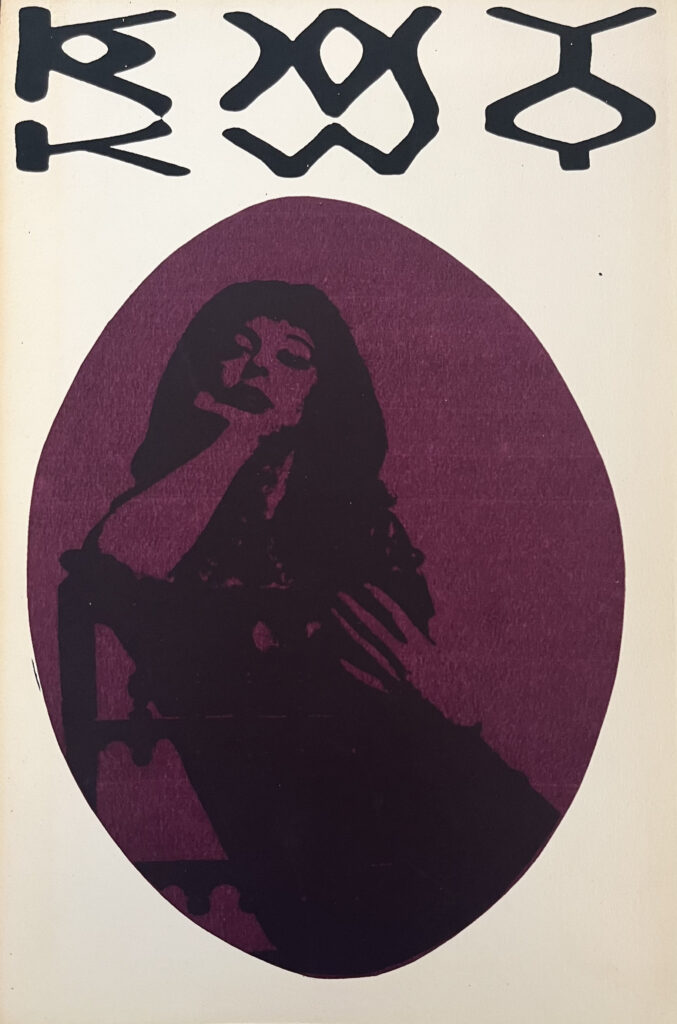

The magazine is a rich, composite art object featuring original silkscreens, photomontages, collages, postcards, soft discs, poetry, theoretical texts, unpublished works and precious documents. Through its 12 issues, we follow the evolution of a group of artists from the informal, gestural or matierist abstraction on display in galleries at the end of the 1950s, to the new art trends in which the group’s members participated – Nouveau réalisme, Nouvelle figuration, Pop art, gestural abstraction, Lettrisme, Fluxus, Art cinétique, poésie concrète, etc. In the background, we can make out their personal, dissimilar paths within the Parisian or international networks, which were then pursued independently in Paris, London, Lisbon, Munich or New York.

First of all, the title, in its lapidary strangeness, intrigues: is it an acronym, an enigma? Voluntarily cryptic, it sounds like an avant-garde code name. However, for the Portuguese who have chosen it, it is endowed with particular meanings: absent from the Portuguese alphabet (until a recent reform), these three consonants take on a sharp meaning, an ironic and political twist, under Salazar’s dictatorship. This absence at the heart of the language speaks both of exile in one’s own country, stifled by censorship, and of exile abroad, where one’s friends are missing. Indeed, KWY was initially conceived as a letter addressed to absent friends… Functioning as both a witticism and a password, this title condenses the avant-garde aspirations and energy that these young people put into their magazine. Its evolution reflects the movement of its members within Parisian and transnational artistic networks.

Perfectly in tune with the times, KWY reflects the artistic and social mutations of a transitional period between the war-torn late 1950s and the forward-looking early 1960s, full of optimism and revolutionary desires.

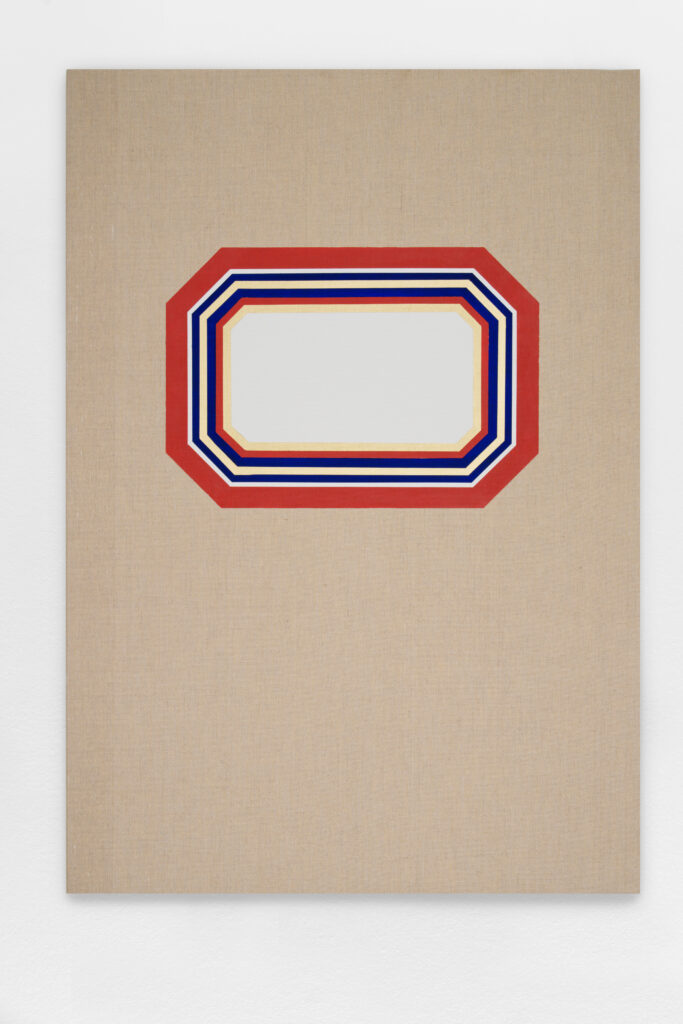

When you browse the issues and look at the attractive, different covers, you’re struck by the magazine’s heterogeneous, cobbled-together character. After all, KWY is an artisanal magazine, entirely hand-made and screen-printed in Lourdes Castro and René Bertholo’s tiny apartment. Heterogeneity permeates every aspect of the publication: paper, format, typography, cover, composition, layout and so on. No two issues are alike. The magazine adopts no recognizable graphic identity or aesthetic; rather, it follows the rhythm of life, of encounters and affinities and, therefore, of the new practices that emerge, as witnessed by the guest list, which diversifies and increases remarkably as the number of pages and copies grows – from 60 to 300, with a peak of 500, but still produced by hand and in a 20 m2.

The originality of KWY’s work lies in its inventive and spontaneous use of screen printing, a process that was still little used in the late 1950s. Motivated in part by cost, the choice of this technique is above all for its experimental potential – color, texture, weft, etc. – which KWY plays with obvious glee. In particular, it exploits the plastic resources of a reproduction process that produces the unique, asserting its specificity with the superlative humor of the advertisement: “The only magazine to offer an original hand-silk-screened work.” Shortly anticipating the developments of this technique by Pop art, it could be described as pre-pop. Nevertheless, KWY is distinguished by an unbridled inventiveness that denotes an improvisation typical of DIY and home economics, but also of youth.

The presence of the hand lends a lively allure to this whimsical publication: technical texts – summaries, bears, titles, announcements of publications or exhibitions, etc. – are all part of the story. The hand is the hallmark of a collective in which individualities mingle on equal terms – everyone puts their hand to the grindstone, bringing their own touch to a highly tactile object. In issue no. 6, which marks a milestone in its development, the editorial team explains its origins, making it clear that the group, which was born of the magazine and has grown up around it, does not represent any particular trend or movement. Thus, the varied, profuse style that marks the magazine’s singularity stems from a disparity intrinsic to the group. KWY was first and foremost a laboratory for experimentation, in the form of a quasi-collective work, displaying a joyful independence from the various aesthetic currents: the freedom for each to choose his or her own style.

The last opus came out in 1964 – it’s the natural fate of magazines and groups to disperse, but it bore fruit, building a bridge between Portugal, Paris and abroad, and weaving around it a web of transcontinental relationships that were, to say the least, varied.

The Autour de KWY exhibition, following on from the Lourdes Castro retrospective I organized in 2019 at the Mrac in Sérignan, brings to light the subterranean dynamics, the forgotten or more confidential filiations of a Parisian and transnational history. As part of my research into Portuguese artists active in Paris in the 1960s-1980s, it includes works by Manuel Alvess (1939-2009), who arrived in the French capital in 1963, where he lived until his death. Retired from the art world, he continued his conceptual and pictorial work, taking over from a Franco-Portuguese migration linked to the dictatorship.

Anne Bonnin, September, 2024